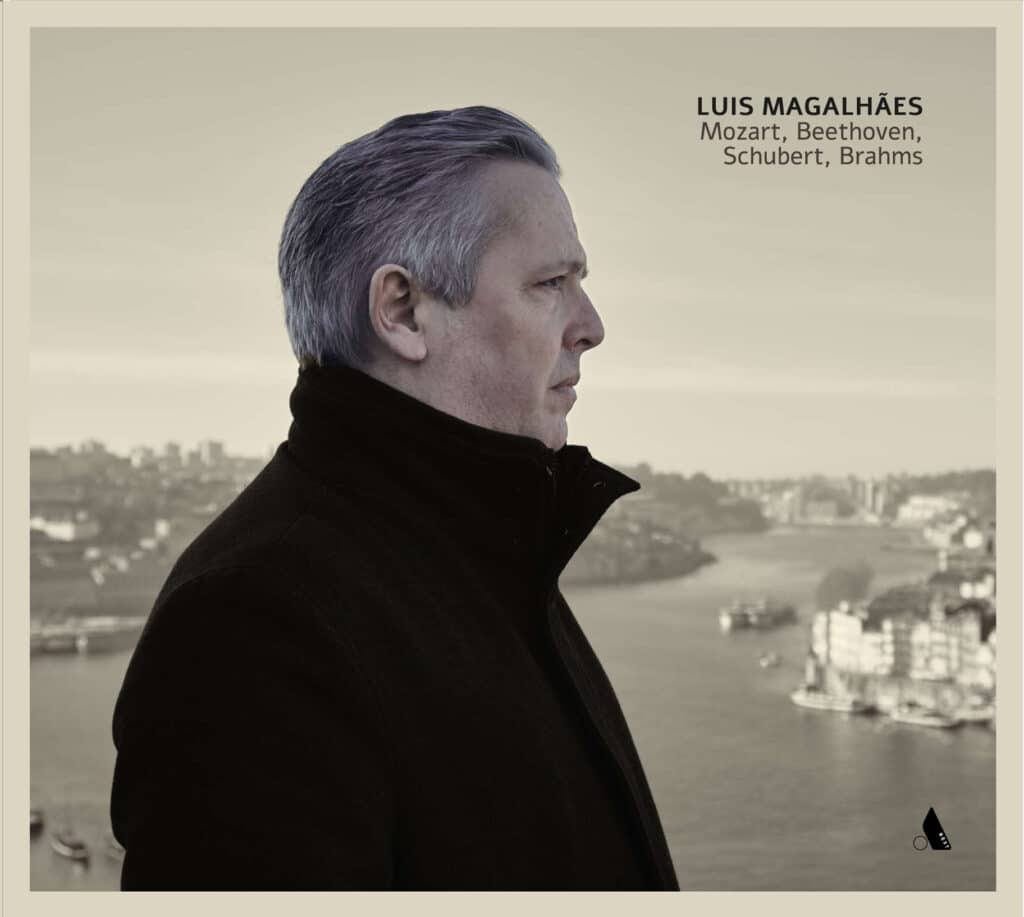

Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms

This recording is, in many ways, a reflection of my own journey—of the moments of clarity and doubt, of resilience and surrender that shaped my life so far. These works by Schubert, Beethoven, Mozart, and Brahms have been my companions for years, sometimes feeling like old friends, other times revealing themselves in ways I never expected. There were days when Schubert’s harmonies seemed to understand me better than I understood myself, when Beethoven demanded more than I thought I could give, and when Brahms reminded me that beauty often lies in contradiction. This album is not just about interpretation, but about a relationship—with music, with time, with myself. I hope that, as you listen, you find your own reflections within these notes.

Tracklist

CD 1

Schubert: 3 Klavierstücke, D.946

1 I. Allegro assai 10:23

2 II. Allegretto 13:38

3 III. Allegro 5:16

Schubert: Sonata in B-flat major, D.960

4 I. Molto moderato 20:40

5 II. Andante sostenuto 10:26

6 III. Scherzo. Allegro vivace con delicatezza — Trio 3:59

7 IV. Allegro ma non troppo 8:38

CD 2

1 W. A. Mozart: Fantasia in D minor, K.397/385g 6:56

2 W. A. Mozart: Fantasia in C minor, K.475 14:25

L. v. Beethoven: 6 Bagatelles, Op.126

3 I. Andante con moto, cantabile e con piacevole 3:59

4 II. Allegro 3:11

5 III. Andante, Cantabile ed espressivo 3:08

6 IV. Presto 4:15

7 V. Quasi allegretto 2:57

8 VI.Presto — Andante amabile e con moto 4:12

J. Brahms: 4 Klavierstücke, Op.119

9 I. Intermezzo: Adagio 4:01

10 II. Intermezzo: Andantino un poco agitato 5:00

11 III. Intermezzo: Grazioso e giocoso 2:10

12 IV. Rhapsodie: Allegro risoluto 4:58