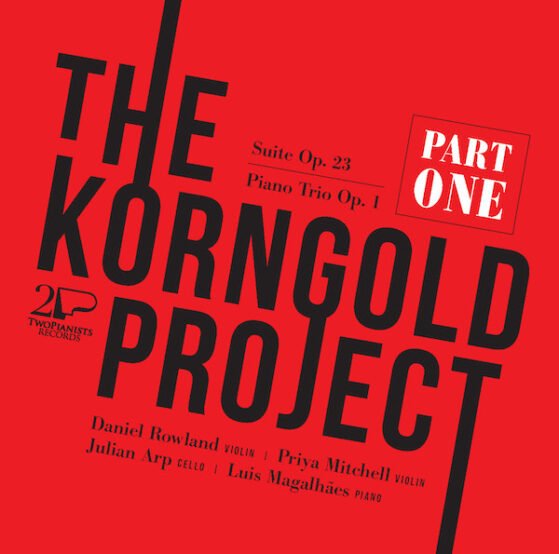

ERICH WOLFGANG KORNGOLD

SUITE FOR TWO PIANOS, CELLO AND PIANO LEFT HAND, OP. 23

PIANO TRIO IN D MAJOR, OP. 1

Violin: Daniel Rowland, Priya Mitchell

Cello: Julian Arp

Piano: Luis Magalhães

James A. Altena

Fanfare, March 2016

I’ll dispense here with all preliminaries about these two remarkable works—the op. 1 penned by an amazing Wunderkind of a mere 12 years of age—and go directly to the finish line. These are absolutely phenomenal performances and recordings, in the jaw-dropping, mind-blowing category of stratospheric excellence. Not merely every bar, but every note, every dynamic shading, is redolent of the fin de siècle Viennese Romantic over-ripeness that is the very quintessence of Korngold’s music. The intense, fierce passion of these performances, seething with the promethean heat of a conjugal embrace, is the sort of thing that one really only encounters (as here) in live performance, and is never quite captured in the studio. The recorded sound is in the demonstration class; it’s as if you are seated in the very midst of the instruments and enveloped in the richness of every overtone. And what richness! Violinists Daniel Rowland (the first violinist of the Brodsky Quartet) and Priya Mitchell, cellist Julian Arp, and pianist Luis Magelhães are a veritable dream team for opulence of tone, precision of execution, and totality of interpretive engagement and emotional communication. It’s not as if either of these works has lacked for excellent champions before. For the suite there is the classic account on Sony with Joseph Silverstein, Jaime Laredo, Yo-Yo Ma, and Leon Fleischer; for the trio my first choice heretofore among several fine alternatives would have been the EMI recording with Glenn Dichterow, Alan Stepansky, and Israela Margalit. But this new entry simply sweeps the boards; every time I listen to it again, I am absolutely stunned by its magnificence. And, best of all, it is advertized as The Korngold Project, Part One. If what is promised to follow can match this, we will have a new reference standard for Korngold’s chamber works. Highest possible recommendation, and yet another prime candidate for my already overflowing 2016 Want List.

Elliot Fisch

American Record Guide, January 2016

Magalhaes plays the raucous and extremely difficult opening passages easily, with excellent tone and expressiveness. …the playing is excellent.

If you are not familiar with Korngold’s music besides his movie scores or his 1920 opera Die Tote Stadt, this excellent recording is a good introduction.

Daniel Coombs

Audiophile Audition, January 2016

Both of these works are a bit of a rarity and they do both meander just a bit. However, this is lovely music played very well by the forces on this recording. Korngold is a composer whose music deserves to be explored more thoroughly.

David Gutman

Gramophone Magazine, November 2015

The results are unfailingly musical, more than adequately spacious and even weepy in the heartfelt ‘Lied’.

Michael Schulman

The WholeNote, September 2015

The Piano Trio…receives a vigorous, upfront performance, recorded live, as was the Suite, with well-deserved applause at its conclusion.

Dominy Clements

MusicWeb International, September 2015

The live performances on this recording are all the more remarkable in that the musicians are far from being an established group. The unity and synergy apparent from this recording makes it rather special, and with good sound quality and barely any perceptible audience noise this is a release that can be purchased with confidence.

Jeff Simon

The Buffalo News, August 2015

The Suite for two violins, cello and piano left hand is a wild, flamboyant and extravagant piece of rare instrumentation that deserves as much stubborn re-affirmation as willing musicians want to give it.

★★★★

Blair Sanderson

Allmusic.com, August 2015

…violinists Daniel Rowland and Priya Mitchell, cellist Julian Arp, and pianist Luis Magalhães play the Suite and the Piano Trio with passion and sensitivity, and give their series an auspicious beginning.

© 2015 Examiner.com

I first encountered TwoPianists Records a little over a year ago after they released a nine-CD box entitled Richard Strauss: Complete Works for Voice and Piano: 1870–1948. I knew nothing about the company other than the fact that the physical CDs were made in Austria. It was only after I visited the Web site that I discovered that the business itself was situated quite some distance from Austria:

TwoPianists Records was founded in 2008 by renowned pianists Luis Magalhães and Nina Schumann, and is based in the stunningly beautiful surroundings of Stellenbosch in the Western Cape province of South Africa.

This past week TwoPianists again came to my attention when I learned that their latest release was entitled The Korngold Project: Part One. It turned out that this project emerged as a result of a gathering of musicians of many different nationalities all coming together to participate in a chamber music festival in South Africa. They discovered that they all shared an interest in the music of Erich Wolfgang Korngold and used the festival setting to give their first performances of music he composed prior to his move to the United States to escape the Nazis. The Web page for this recording on the TwoPianists Web site continues this story as follows:

Such was the success of their virgin Korngold performances that they vowed to travel the world to complete the Korngold project. And so they embarked on a journey that included rehearsing in Berlin, performing in Oxford and finally concertizing and recording in South Africa. This is not an established group but a meeting of minds linked through the beauty of Erich Korngold’s music.

To be fair, these musicians are not the first to have taken an interest in Korngold’s music. The Beaux Arts Trio recorded his Opus 1 piano trio in D major in 1992; and, in my home town of San Francisco, it has not been difficult to find performances of Korngold’s chamber music, songs, and his opera Die tote Stadt. Furthermore, if one overlooks the film scores he composed after his move to the United States, his catalog is relatively modest: the opus number count only runs to 42.

Part of the problem may be that Korngold never really kept up with the times. As a child prodigy Korngold played a cantata he had composed for Gustav Mahler, who was impressed enough to recommend him for study with Alexander von Zemlinsky, who also taught Alma Schindler before she married Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg (who would marry Zemlinsky’s sister Mathilde). I have previously described the Opus 1 trio as having been “written at the time that the composer was of bar mitzvah age.” Stylistically, however, Korngold was best known for taking the lush outpourings of the twilight of Romanticism and pumping them up with a fresh round of steroids, which may explain why his music critic father Julius once chastised him with the warning “Don’t bathe!” The younger Korngold’s approach certainly served him well with the film industry; but, when he returned to Europe after the end of the Second World War, he realized how out of touch he had become with modernist advances.

Nevertheless, there is much to enjoy in Korngold’s music as long as one is willing to take an it-is-what-it-is approach. The contributors to this new TwoPianists release, pianist Magalhães, violinists Daniel Rowland and Priya Mitchell, and cellist Julian Arp, do just that. Their performance of the Opus 1 trio is a reflection of their youthful enthusiasm, which is certainly consistent with the exuberance of the composer’s age at that time. Rowland is occasionally a bit shaky with his intonation, particularly on some of the longer sustained notes; but all three players are definitely true to the spirit of the music.

The other selection on this recording is the Opus 23 suite for two violins, cello, and piano left hand. This was composed for Paul Wittgenstein, a celebrated pianist who lost his right arm during World War One. Wittgenstein came from a well-to-do family; and he is now known for having commissioned a generous number of compositions that could be played by the left hand alone. Korngold was actually the first composer he approached, and that first commission resulted in his Opus 17 piano concerto in C-sharp major. Wittgenstein was not phased by the key signature and presented Korngold with a second commission, whose result was the Opus 23 suite.

Ironically, while this suite played a major role in the journey of discovery of its performers on this recording, I was in a position to enjoy it as the piece of Korngold chamber music I knew best. I had encountered it not only through a recording, discussed on this site in February of 2013, but also (and far more exciting) through a student chamber music recital in November of 2010 at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. (For the record my first encounter with Korngold’s chamber music came about half a year earlier through his third string quartet, which he composed after his move to the United States.)

It is easy to imagine that Wittgenstein was as pleased with Opus 23 as he had been with the Opus 17 concerto. The opportunities for virtuoso display are legion, and Korngold shows a clear understanding of just how much the left had can do on its own. It would also be fair to say that there is far more rhetorical breadth in this suite than there had been in the youthful Opus 1 trio. Nevertheless, at the hands of the performers on this recording, both pieces stand firmly on their own respective merits; and, from a personal point of view, I have to say that I found myself taking delight in how another group of performers was enjoying the same discovery process that I had encountered from those conservatory students in San Francisco.

The question now, however, is one of where this project will go next!

© 2015 Infodad.com

The music of Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897–1957) is undergoing something of a reconsideration these days, and TwoPianists Records is poised to play a significant role in it through a series it is calling The Korngold Project. The first volume includes Korngold’s only Piano Trio, which is his first published work and was written when he was just 13—showing him as a Mendelssohn-like prodigy. The trio was written when Korngold was studying with Alexander Zemlinsky, and it contains both late-Romantic intensity and high levels of lyricism. It also has some clever compositional elements, to which the performers are careful to pay close attention: notably, it has an almost circular structure, with the work’s opening theme repeated and reworked at the conclusion of the finale. Although it is easy to hear echoes of Brahms and Richard Strauss in the music, there is nothing overtly imitative in it, and its harmonic language is right in line with what would be expected for its time period (1909–10), showing that Korngold understood very early in life the direction in which music was going—even if he often chose in later works not to go that way. The Suite for Two Violins, Cello and Piano Left Hand is later Korngold (1930) and significantly more mature in the sense of being written in a more-definitive, more-personal style. But it too draws largely on late-Romantic notions of harmony and emotional communication, and its five movements are evocative of exactly what their titles suggest: Präludium und Fuge, Walzer, Groteske, Lied and Rondo-Finale (Variationen). It was commissioned by pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who lost his right arm in World War I and was very pleased with the left-hand concerto that Korngold had previously written for him. Less thoroughly integrated than the early Trio, as befits a work labeled a suite, this piece gives the performers plenty of chances to showcase their individual parts (including a very demanding opening piano cadenza) as well as their ensemble work—Korngold was skilled at creating equal contributions to chamber music for all the participants. This entry in the budding Korngold revival bodes very well indeed for future releases in the same series.